Abtracts

Jacques Jubé’s Expedition to Moscow, 1728-32: A Mission Impossible?

The Abbé Jacques Jubé (b. 24 or 27 May 1674 in Vanves, d. 30 December 1745 in Paris) was of humble origins but led an adventurous life. He has a short entry in the Grande Encyclopédie, inventaire raisonné des sciences, des lettres et des arts, volume 21 (1895), p. 233, which hints at some important aspects of his life, though it does not do him justice:

‘He took part in the Formulary affair and published a leaflet entitled Pour et contre Jensenius, touchant les matières de grâce (‘For and Against Jansenism, Touching on Matters of [Divine] Grace’, Paris, 1703) which was seized by the police [and twice nearly got him arrested]. His church at Asnières [near Paris] was a refuge for all other priests under investigation [by the police]. Furthermore, Jubé had removed from his church all images and religious ornaments: he also modified the liturgy and required of his parishioners that they lead a strict, disciplined life; notwithstanding this, they held him in high regard. He was soon persecuted by the authorities and had to flee the country. He went first to Rome, then to Holland and even to Russia, doing the rounds and spreading the doctrine of Jansenism.’

[Author's translation]

What this short entry does not say is that the Abbé Jacques Jubé (or Jubé de la Cour – his assumed name, adopted while being pursued by the authorities in France) had a double, secret mission, entrusted to him by the Doctors of the Sorbonne. His brief was to go to Moscow, where he was to lobby highly-placed aristocrats close to Emperor Peter II to further the cause of reunion between the Catholic and Russian Orthodox churches. When Jubé set out for Russia, he had no idea that Peter would die shortly after his arrival in Moscow and that he would have to deal with the rather difficult new ruler, Empress Anna Ioannovna. He was to carry out this mission incognito, under the official pretext of working as a private French tutor to two of the sons of the diplomat Prince Sergei Petrovich Dolgorukov (1696-1761) and his wife Princess Irina Petrovna née Golitsyna (1700-51), who had secretly converted to the Catholic faith while the prince was resident with his family in The Hague, working as a diplomat. Jubé was also tasked with nurturing the tender shoots of the family’s newly found Catholic faith, as their resident father confessor and mentor – a mission which, apart from his other secret assignment, was enough alone to get him unceremoniously thrown out of Russia by Anna Ioannovna.

The very fact that Jubé would be living on the Dolgorukovs’ estate at Nikol'skoe-Uriupino in the western outskirts of Moscow, as a guest of such influential aristocrats connected to two of the most powerful clans close to the Russian throne, who rose to the height of their power and political influence under Peter II, gave those who longed to see the Catholic and Orthodox Churches reunified cause for considerable optimism. They believed that the time was ripe and the circumstances propitious for tackling this delicate issue again, though it had failed so many times in the past. New hope sprang in the hearts of a group of eighteen doctors of the Sorbonne, who had been pleasantly surprised and encouraged by Peter I’s reaction to this delicate matter when it was raised during his visit there on 14 June 1717.

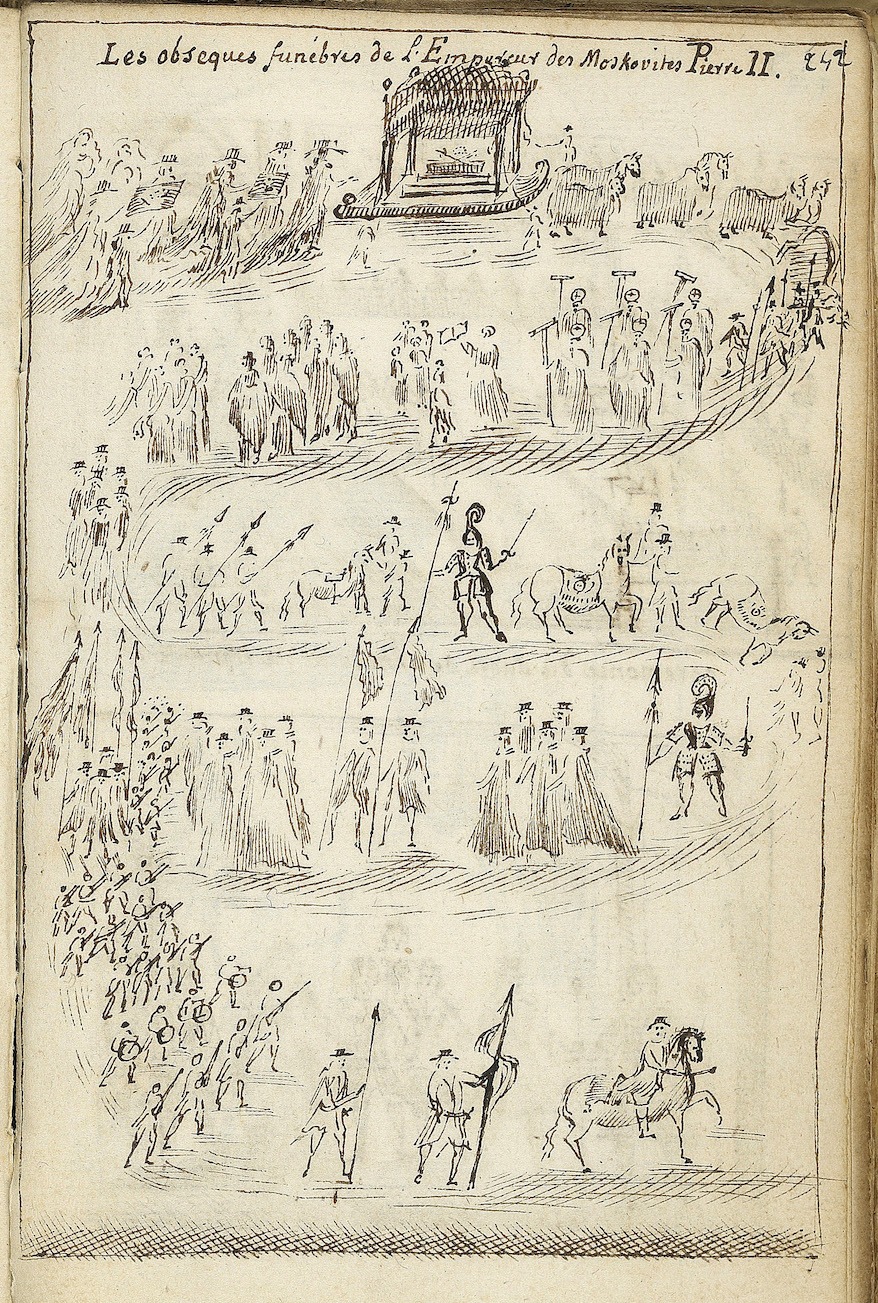

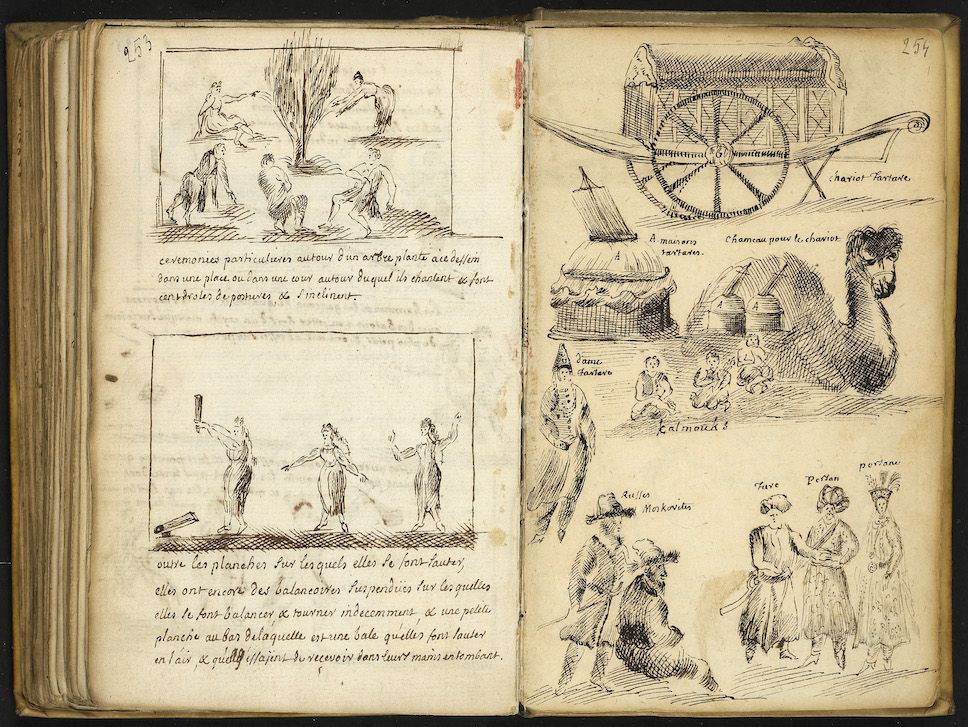

Jubé left an unpublished account or 'journal' of the trip that he made to Moscow, where he arrived late in 1728 and stayed for just over three years, until Empress Anna Ioannovna gave him orders to leave Russia at short notice. His journal languished in an archive in Rouen Municipal Library among the papers of Eugène Coquebert de Montret (1785-1847), an orientalist, diplomat and polymath, though its existence was known through references in other sources, but these are few and rather obscure. It was rediscovered by Michel Mervaud, a professor of history at Rouen University, who transcribed the small journal and added a highly informative, substantial Introduction, with copious annotations, and the volume was published in 1992 by the Voltaire Foundation, Oxford. Mervaud also published two articles on Jubé’s journal and adventures in Russia. Fortunately, there also exists a collection of Jubé’s letters in the archive of the Bibliothèque municipal de Troyes, which sheds light on Jubé’s personal life, about which information from other sources is scant. Jubé’s eye-witness account has been mentioned in the Dictionnaire historique, littéraire et critique (Avignon, 1759, vol. III, p. 937) as a ‘precious work, of which the public should not be deprived any longer, and which is particularly useful for recording the present state of religious faith in a large part of Europe, which the Christian traveller [i.e., Jubé himself] has not investigated with the eye of superficial, sterile curiosity, but with that of a man of keen, enlightened faith’. [Author's translation] Hence, his journal is both personal and historically important, for Jubé arrived in Moscow, serendipitously for the historical record, in time to attend both the funeral of Peter II and the coronation of Anna Ioannovna, which are both described and illustrated by him in his journal.

As he applied himself with his customary energy and dedication to his covert mission for reunion, Jubé rubbed shoulders with, and personally got to know, prominent members of the Dolgorukov and Golitsyn clans, leading clerics such as Feofan Prokopovich and other metropolitans appointed to Peter I’s Holy Synod, and intellectuals such as Antiokh Kantemir, who all had a presence at the Court. He was also a kind of ‘on-the-spot’ reporter of the first wave of Empress Anna’s spiteful revenge, which she wrought upon prominent members of the Dolgorukov family, as she made them pay for their temerity in trying to constrain her autocratic powers during the succession crisis caused by Peter II’s untimely demise.

Jubé was assisted in his mission by two other important foreigners who happened to be in Moscow at the time and with whom he shared his secret. The most influential and best-placed of them was the Spanish ambassador to Russia, the Duke of Liria (or Lihria), appointed by King Philip V of Spain. The other was Father Ribera, a Spanish (Catalonian Dominican) priest attached to the embassy in Moscow, who said mass for the small Catholic community there. The Duke of Liria himself left an important diary of his tour of duty in Russia, which has been as neglected by historians and scholars as Jubé’s own. Liria arrived at St Petersburg on 23 November 1727, just before the Court moved back to Moscow at Peter II’s behest (and/or under pressure from the old guard) and just over a year before Jubé himself arrived at the old capital in December 1728. As Spanish ambassador, Liria was on friendly terms with Baron Osterman and Prince Ivan Alekseevich Dolgorukov, Peter II’s favourite and inseparable companion. By the time Jubé arrived, Liria had already established a network of friendships and contacts in high places, including the young tsar himself, and Jubé was able to take advantage of these connections for furthering his cause. It goes without saying, of course, that Liria had also made some enemies, which was almost inevitable at Anna’s Court pack-full of foreigners whom the Russian conservative lobby hated. Jubé himself was to feel their jealousy and contempt, not least because it was known that he was a Catholic to boot.

Before undertaking his trip to Moscow, Jubé left the environs of Paris and his parish for self-imposed exile in The Hague, for his own safety, where he first met the Dolgorukovs. He could have easily ended up in the Bastille for his Jansenist proselytizing during a period when the Catholic Church in France was in a state of turmoil and riven by a dispute that started out as theological and later developed into a political struggle between Pope Clement XI, his successor and the French throne. Clement XI issued the divisive bull Unigenitus in September 1713, condemning Jansenism. The main theological issue was the contentious argument over predestination as propounded by Jansen, Bishop of Ypres, in 1640. It was regarded as a theological aberration by successive popes and many prominent bishops around France, but in Paris Jansenism found support among highly placed clerics, including many doctors of the Sorbonne. The issue would simply not go away and it rumbled on for decades with increasing acrimony and ramifications. The political struggle which stemmed from it was encapsulated in the French movement known as Gallicanism – the debate over the monarch’s or the State’s authority versus papal authority, the obverse being known as Ultramontanism. And as it turned out, this 'clash of the titans' was akin to Peter I’s own heart and thinking, since he had taken on the Russian Orthodox Church hierarchy in 1721, with his Духовний регламент or 'Ecclesiastical Regulation', which brought the whole institution under state authority and placed Peter firmly in charge. The emperor had already dispensed with patriarchs after the death of Patriarch Adrian in 1700. Hence, there are parallels between church-State relations in France and Russia around this time, and no wonder that the Sorbonne doctor M. le Régent was able to comment in conversation with Cardinal Noailles (Bishop of Paris) that he found Peter quite well informed about the Unigenitus affair when he visited the Sorbonne, which makes Peter look rather coy and not entirely honest when he shied away from commenting in detail on this occasion, remarking dissmissively, ‘I’m only a soldier’.

Clearly, history shows that Jubé did not manage to further the reunification of the two Churches, and since that time the rifts between the Catholic and the Russian Orthodox churches have remained as wide and unbreachable as in his era, and even long before him. Despite all good intentions and hopes to the contrary, realistically it was always likely to be a lost cause, since both institutions were and are entrenched in traditions and interpretations of holy writ, convinced that theirs is the only singular truth, though to those less dogmatic on these issues, the contentious points seem small and even surmountable. There appears to be more to this recalcitrance than theological exegesis.

However, what has come to light from this episode in history, thanks to, primarily, ‘la superbe publication de Michel Mervaud’ (to quote one reviewer) and the work of others, is the rediscovery of Jubé’s journal. It comprises 266 small-format folios and many of the latter pages contain his own charming pen-and-ink drawings which embellish his detailed descriptions of whom he met and what he saw, covering a far wider ambit than religious and church affairs. We must no longer neglect the Duke of Liria’s own, equally detailed memoir, which has attracted even less attention than Jubé’s. Taken together, they constitute a valuable resource of an under-studied period of Russian history and throw an interesting light on relations between France, Russia, and Spain.

- David Holohan, formerly of University of Surrey

david.holohan@blueyonder.co.uk

NB. Dr Holohan is currently preparing a book-length study of Jubé’s life and journal, including a first English translation of his text, with all the original illustrations penned by him. He is also producing a translation of the Duke of Liria’s memoir, fully annotated and with an Introduction.

Back to the contents page.