Notes

Russian Empresses and their Foreign Counterparts: The Validation of the New Title of the Russian Ruler in illustrations of David Fassman’s 'Dialogues of the Dead'

In 1721, Russia proclaimed itself an Empire. The Imperial title of the Russian ruler was immediately acknowledged by only two European states – Prussia and the Dutch Republic – then soon after by Sweden. Further diplomatic recognition by other European states stretched across almost half a century. The new title reflected exceptional ambitions of the country which had begun a process of forced 'Europeanisation' just two decades previously. The Russian Imperial title became the subject of an agitated discussion during the eighteenth century, both on an official (that is, political and diplomatic) level and on a cultural level, through literature and the fine arts.

The dialectically-charged literary genre known as 'Dialogues of the Dead' contributed to this discussion of the new title. While the origins of this genre lay in Classical Antiquity, it was revived during the Renaissance and remained popular until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The form commonly consisted of a debate on philosophic, moral or political topics between by famous historical figures in the afterworld. A significant example of this genre are the Gespräche in dem Reiche derer Todten (Dialogues in the Realm of the Dead) by David Fassman (1683-1744). Hans-Christof Kraus has described Fassman as 'a soldier, secretary, publicist, writer, translator, [and] court historiographer with [an] adventurous life' (Soldat, Sekretär, Publizist, Unterhaltungsschriftsteller, Uebersetzer und Historiograph mit abenteuerlichen Lebenslauf).[1] Fassman edited these 'Dialogues' on a monthly basis from 1718 until 1740, overal a total of 240 'Gespräche' ('Dialogues'). They were intended to provide the poorly educated with an idea of ongoing political affairs and enjoyed considerable popularity.

A year ago, Stephanie Dreyfürst published a brilliant in-depth study of Fassmann’s 'Dialogues', which has provided a revised method of exploring them.[2] However, her work offers a fresh understanding of the principal problems illustrating the main points of the 'Dialogues' through a thorough analysis of several examples, rather than a meticulous analysis of the entire series. Therefore, Fassman's 'Dialogues' still provide useful possibilities for further research, especially in the interpretation of the 'Dialogues' concerning specific countries in their contemporary political context with the aid of new methodology. This article examines the 'Dialogues' featuring characters from Russian history, which have not yet been comprehensively analysed, although some attempts to explore their meaning were undertaken by Eckhard Matthes (1987)[3] and Nicoletta Marcialis (1989).[4] Moreover, the illustrations that accompanied these 'Dialogues' have never been analysed in their own right. My argument focuses on the question how the newly-acquired Imperial title of the Russian ruler was reflected in juxtaposition between the immediate successors of Peter the Great and their foreign counterparts, particularly in the illustrations. As Dreyfürst has suggested, Fassman always introduced two characters in his pieces, a trait inherited not only from the tradition of the 'dialogues of the dead', but also from Plutarch’s Vitae parallelae ('Parallel Lives'). Thus, such an analysis promises to be fruitful. The subject of this article are illustrations accompanying three 'Dialogues':

- between Empress Catherine I and the Eastern Tsarina Zenobia;

- between Empress Anna Ivanovna and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire Charles VI;

- between Empress Anna Ivanovna and Queen Elisabeth of England and Ireland.

NB. Peter II, the first Russian ruler to be crowned Император, is also important in this context, but in Fassman’s series he appears in a 'Dialogue' with his father Aleksei Petrovich, rather than with a foreign monarch.

The theme of the title of the Russian ruler first arose in 'Dialogues' featuring Peter the Great — four 'Dialogues between the remarkable tsar of Moscow Peter the Great and the great tyrant Ivan Vasilievich II' (83-86 Entrevuë, 1725) and 'A Noteworthy Dialogue between King Charles XII and the tsar Peter the Great' (1728). While these controversial pieces require careful examination, they are not the focus of this article, save to note that in the title Peter is called 'tsar', rather than 'Emperor' (although in a picture accompanying the 'Dialogue' with Charles XII he is depicted in an Imperial crown) which is indicative of the fact that the practice of referring to the Russian ruler as such has not yet been established.

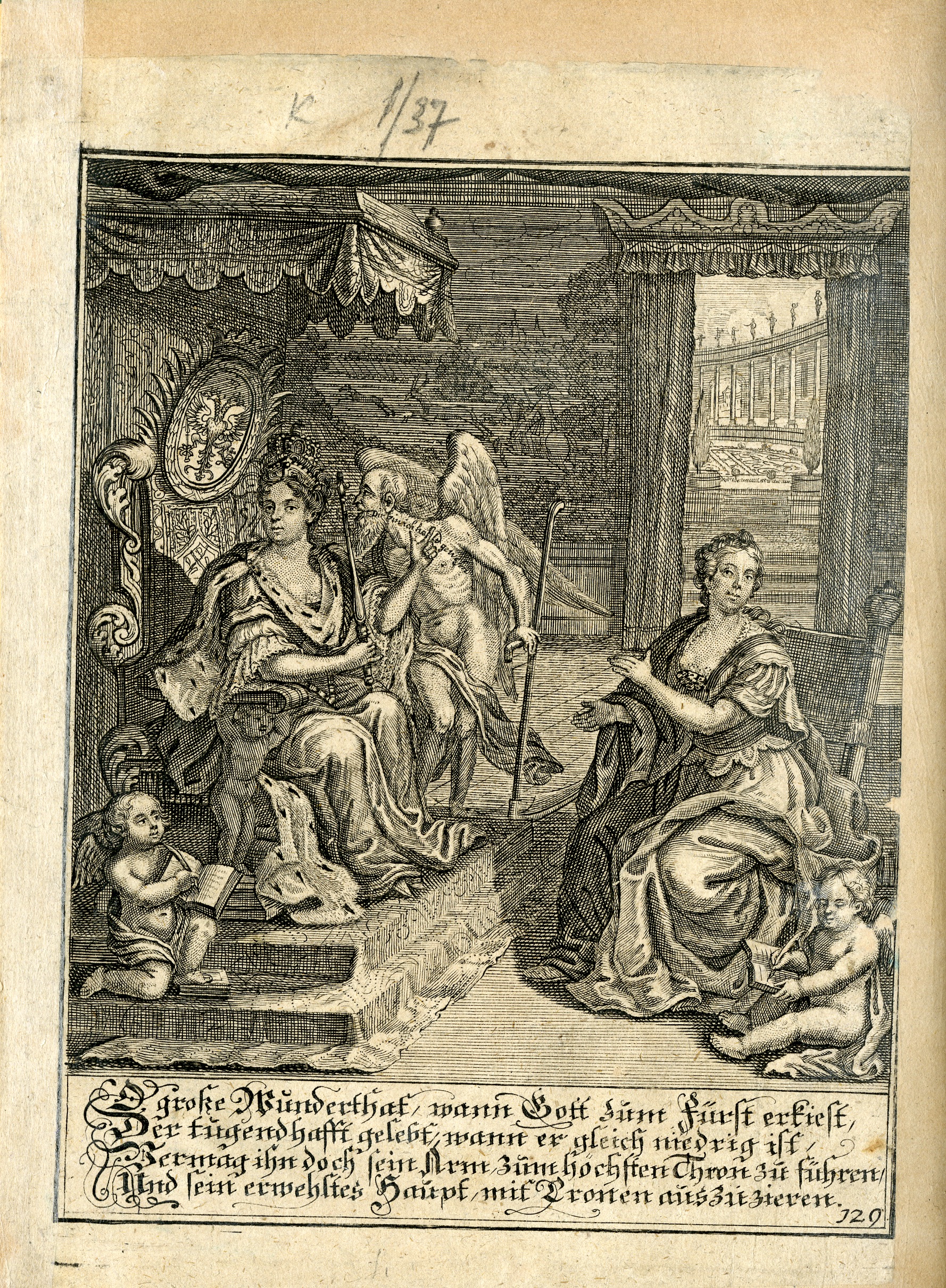

Instead, in Fassmann’s series, this usage occurs for the first time in 'A Dialogue... between Empress Catherine and... the Eastern Tsarina Zenobia' (1729). Here, the Imperial title of the Russian ruler is declared in the title of a piece (Illustration 1). Different designations of a Russian ruler did coexist, but here they emerge in a succession of literary pieces by the same author, thus indicating certain evolution.[5]

As it is explained in the texts that Catherine and Zenobia, Queen of the Palmyrene Empire who lived in the 3rd century AD, invite comparison. They both followed their husbands in military campaigns, both were revered by soldiers for their kindliness, and finally both visited Persia. Fassmann had already introduced Catherine I to the readers in a Dialogue between Peter and Ivan, 83 Entrevuë. While he was circumspect in his statements about the origin and early years of this 'Russian Cinderella', the empress was nevertheless irritated and Fassman had to leave Carlsbad to take refuge in Bayreuth. Moreover, an anonymous response to it did appear in Russia refuting Fassman’s 'libel' — <и>Разговор между трех пирятелей сошедшихся в одном городе, а именно Менандра, Таландара и Варемунда.[6] Subsequently, after Catherine I’s death, Fassmann repeated the same story in his 'Dialogue'. He emphasised that the destiny of a person elevated from a humble position to the very top of the social hierarchy for their personal qualities deserved deep admiration. However, Fassman also sought to capture his readers' attention by reiterating some curious details of her life.

Nevertheless, the engraved frontispiece is unambiguous in conveying the idea of Catherine I's high status. Whereas 'Empress' Catherine is depicted on a throne under a canopy, the 'world-famous' tsarina Zenobia has to be content with a place at the foot of the throne. Moreover, Zenobia meets Catherine’s speech with applause thus expressing praise. Equally notably, in the text, they are depicted as acting like equals, while the picture stresses Catherine’s superiority.

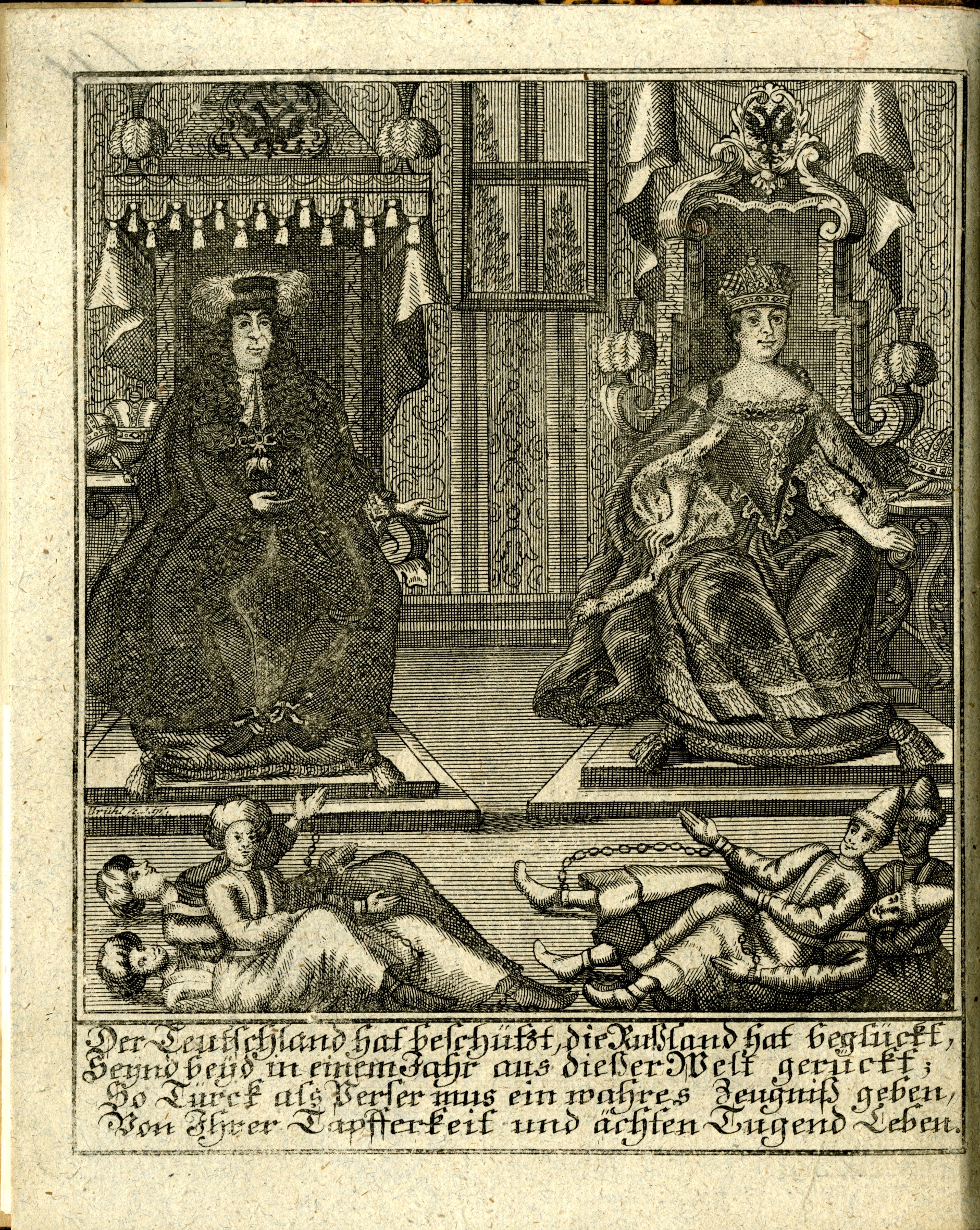

Two of Fassman’s 'Dialogues' describe posthumous meetings with foreign rulers of Empress Anna Ivanovna. In one of them, she converses with Elisabeth I of England and Ireland (1558-1603); in the other – with the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire Charles VI (1711-1740). The names of both rulers show the growth of international prestige of the Russian Empire, as reflected in Anna’s title. In one case, she is called 'Kayserinn und Selbst-Halterin aller Russen' and in the other — 'Allerdürchlautisten / Grossmächtigsten Kayserin und Gross-Fürstin, Frauen Anna, Kayserin, Gross-Fürstin and Selbst-Erhalterin von Russland'.

The choice of such collocutors as Charles VI and Anna Ivanovna (Illustrations 2 and 3) was far from coincidental. In the text, it is explained by the fact that they were allies in the war against Turkey. But, in reality, a rivalry lay behind this alliance. A telling example is a comment on 'The General Plan of the War' with the Ottoman Porte (1735-1741) by Field-marshal Count Burkhard von Münnich. The goal of this war was to capture Istanbul and then to crown Anna Ivanovna as the Greek Empress in Hagia Sophia. 'And who would then ask, to whom does the Imperial title by rights belong? To the one, who is crowned and anointed in Frankfurt [i.e. Charles VI] or in Istanbul?'. In the end, the war finished with relatively humble results for Russia. However, this does not alter the fact that the nascent Russian Empire competed with the Habsburg Empire over the authenticity of the exceptionally prestigious title – Emperor – which could, properly speaking, be assigned to only one state.

The idea of the parity of Russian and Austrian ruler is clearly presented in the illustration. The composition is symmetrical and isocephalic. Both rulers sit on the thrones under canopies, with double-headed eagles above them. Both Austria, a successor of the western Roman Empire, and Russia, an inheritor of the eastern Roman Empire, used the same coat-of-arms which was considered to be a symbol of the great Roman past, despite the fact that a doubled-headed eagle had never been the coat-of-arms of either Rome or Byzantium.

The portrait of Anna Ivanovna is defined by Dmitrii Rovinskii as belonging to 'Louis Caravaque’s type'. As a matter of fact she looks different in two editions of the 'Dialogue' which appeared in the same year (1741). In the one edited in Braunschweig and Leipzig (ill. 2), the engraving is of a rather poor quality, but the empress’s face certainly resembles the Caravaque type. The engraving from the Magdeburg edition (Illustration 3) is more skillful. In it, Anna’s face has a remote likeness to Caravaque’s type, but her image is lovely and endearing — a rarity in this empress’s iconography! Notably, both images are in fact primitive copies of J. C. Sysang’s rare engraving Anna von Russland (see this copy, held in the Stadtbibliotek Trier) [Accessed: 26.06.16] This is a unique Rococo portrait in which Anna appears graceful, even coquettish, holding her scepter in an exquisite gesture with a little finger apart. The posture, her costume, and the form of the throne are the same, albeit simplified.

The 'Dialogue' of Anna Ivanovna and Elisabeth I of England (Illustration 4), implying their comparison, was a form of prelude to the introduction of the image of the English queen in Russian literature of a later period. The image of Elisabeth I was interpreted in the context of mythical-poetical (or rather mythical-political) semantics of the Astraea story. It originated in Eclogue VI of Virgil’s Aeneid and subsequently became a key attribute of Imperial symbolism. The Roman poet linked the beginning of the Golden Age with the advent of the Virgin (Astraea) and the birth of the divine baby. Symbolism of Astraea reached its pinnacle in the English culture of the sixteenth century when, in the name of Astraea, poets in fact glorified the Virgin-Queen Elisabeth. The beginning of the Golden Age was associated with England’s attainment of naval supremacy over Spain. The destiny of Virgil’s metaphor in eighteenth-century Russia has been thoroughly examined by Vera Proskurina. Somewhat predictably, the symbolic political overtones of Astraea were deployed in Russian art of that period because of a series of female rulers and the ambiguities in the order of succession. Proskurina traces the image of Astraea to Mikhail V. Lomonosov’s ode dedicated to Ivan VI Antonovich and his mother, the regent Anna Leopol'dovna, and the literature of the succeeding reign of Elizaveta Petrovna. Notably, Empress Elizaveta Petrovna was likened not only to Astraea, but also to Elisabeth of England because of her single status and name. After the short reign of Emperor Peter III, the penchant for such allegorical allusions regained its strength during the reign of Catherine II – firstly in connection with the minority of Grand Duke Paul and the question of her role as that of regent, and then subsequently in relation to the glorious naval victories against the Ottoman Empire.

The introduction of Fassman’s 'Dialogue... of Elisabeth and Anna' into this context reveals the earlier emergence of allusions to the image of Astraea with respect to Russia. They appear for the first time regarding Empress Anna Ivanovna, not Anna Leopol'dovna, although not explicitly, but rather through the image of Queen Elisabeth I of England. The image of the latter had already been introduced in Russian literature of the seventeenth century – albeit with no connection to the Astraea myth at that time, of course — with Silvestr (Simeon A. Medvedev) comparing tsarevna Sofiia Alekseevna to several glorious female rulers, including 'Елисавеф Британска'.[7]

In Fassmann’s text, the comparison of Anna and Elisabeth is based on the fact that neither woman could expect that they would inherit the throne. While Astraea is not explicitly mentioned in the text, it evokes certain associations with such a compleх of ideas around the mythology. They are further developed in the illustration. The empress and the queen are portrayed upon the background of the sea dotted with ships. The importance of the seascape in the composition is accentuated by a curtain drawn aside and pointing gestures of the rulers, meaning that the theme of naval glory is associated not only with Elisabeth. In reality, there were not many naval battles during the Russian-Turkish war of 1735-1739 and they were not really glorious for Russia. But in the 'Dialogue', Elisabeth appears naturally curious about them and Anna, after admitting defeat in one of them, tells her about the Russian naval victory which marked the end of the war. Notably, this is the first example of a portrait of a Russian empress projecting a military, masculine image — although in female dress, Anna has some elements of male/military costume. Anna Ivanovna wears a chain of the Order of St. Andrew and holds a marshal’s baton in her hand. The Imperial crown is depicted resting on a cushion, while the head of the Empress is surmounted with a distinctive military hat. Such a deliberate choice of a headdress certainly reinforces the martial theme: i.e. through the war with the Ottoman Porte to the genuine Empire. This type of symbolic portrait further developed during the reigns of Elizaveta Petrovna and Catherine II.

Fassmann’s “Dialogues…” were created in Leipzig, in Saxony, which enjoyed friendly relations with Russia. For example, Anna Ivanovna provided military support for Friedrich August II of Saxony's successful bid to become the King of Poland. Later, during the Seven Years War, Saxony was also among Russia’s allies. This can partially explain the emphasis on the high status of Russian Empresses in Fassmann's works.

- Ekaterina Skvortcova, Institute of History, St Petersburg State University

e.skvortsova@spbu.ru

NOTES:

[1] H.-Ch. Kraus, Englische Verfassung und politisches Denken im Ancien Règime 1689 bis 1789 (München, 2006), 345.

[2] S. Dreyfürst, Stimmen aus dem Jenseits: David Fassmanns historisch-politisches Journal "Gespräche in dem Reiche derer Todten" (1718-1740) (Berlin & Boston, 2014).

[3] E. Matthes, 'Das veränderte Ruβland und die unveränderten Züge des Russenbilds', in M. Keller (ed.), Russen und Ruβland aus deutscher Sicht. 18. Jahrhundert: Aufklärung (München, 1987).

[4] N. Marcialis, Caronte e Caterina: dialoghi dei morti nella letteratura russa del XVIII secolo (Rome, 1989).

[5] I. de Madariaga, 'Tsar into Emperor: The Title of Peter the Great', in Politic and Culture in Eighteenth-Century Russia: Collected Essays by Isabel de Madariaga (London & New York, 1998), 15-39.

[6] Marcialis, Caronte e Caterina, 58-61.

[7] Сильвестр [Медведев], 'Подпись к портрету царевны Софьи (1687)', в В. П. Адрианова-Перетц (ред.), Русская силлабическая поэзия XVII-XVIII вв. (Ленинград, 1970), 201-2, 192-3, 411.

ILLUSTRATIONS:

Illustration 1: Catherine I and Zenobia. Frontispiece. [Fassman D.] Gespräche in dem Reiche derer Todten … zwischen der Rußischen Kayserin Catharina, und der weltberühmten Orientalischen Königin Zenobia. Leipzig: Deer, 1729. ©Russian National library, Saint-Petersburg.

Illustration 2: Karl VI and Anna Ioannovna. Frontispiece. [Fassman D.] Erster Theil des Gespräches im Reiche derer Todten, zwischen dem Allerdurchlauchtigsten Großmächtigsten unüberwindlichsten Kayser, Fürsten und Herrn, Carolo VI des Heil. Römischen Reichs erwehlten Kayser, Könige zu Ungarn und Böheim, Erzherzoge zu Oesterreich und der Allerdürchlautisten Großmächtigsten Kayserin und Groß-Fürstin, Frauen Anna, Kayserin, Groß-Fürstin and Selbst-Erhalterin von Russland. Braunschweig und Leipzig: [s.l.], 1741. ©Russian National library, Saint-Petersburg

Illustration 3: Karl VI and Anna Ioannovna. [Fassman D.] Erster Theil Des Gespräches im Reiche derer Todten, zwischen dem … Kayser, Fürsten und Herrn, Carolo VI und der … Kayserin und Groß-Fürstin, Frauen Anna... Magdeburg: Gottfried Bettern, 1741. ©Russian National library, Saint-Petersburg.

Illustration 4: Elisabeth and Anna Ioannovna. Frontispiece. [Fassman D.] Gespräch im so genannten Reiche der Todten, zwischen Elisabetha, Königin von England und Ireland, und Anna Ivanowna, Kayserinn und Selbst-Halterin aller Russen. Franckfurt-am-Mayn: Heinrich Lüdwig Brönner, 1741. ©Russian National library, Saint-Petersburg.

Back to the contents page.